Although India is often viewed as a stereotypically vegetarian nation, such assessments have proven to be false in recent years. In fact, reports indicate that only 23% to 37% of the total population is vegetarian, so India is largely a nation of omnivores. In addition, we’re also the largest global producer of milk, contributing to around 22% of the total milk production.

As these facts indicate, vegetarianism is therefore a minority practice in India thus far. But of course, regular meat consumption varies from household to household, and from state to state. Statistics vary with regard to lactose intolerance among Indians as well; some reports say it is around 33%, while others say it is closer to 60% to 70% (although this does not mean that people who are lactose intolerant necessarily avoid milk products).

All this is to say that the nation’s approach to plant-based eating and ethical food consumption is quite complicated at present, and requires some unpacking. You’ve probably heard the term ‘vegan’ before, but what does it mean, and has it become a movement of sorts in India?

What is Veganism?

Image By Tischbeinahe

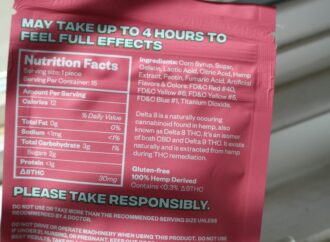

Vegans may define their eating habits and lifestyle in different ways, but if we are speaking generally, veganism is a form of living that refuses to participate in animal exploitation. Often, vegans who fully embrace the lifestyle will not just cut all animal food products out of their lifestyle, but they will also avoid wearing clothes made from animal fur or skin (such as leather). Some vegans may do this out of a dislike for animal cruelty, but many might also go down the vegan route because of a larger concern for the environment and the climate crisis. Others turn vegan for health reasons.

Whatever the motivation behind becoming vegan may be, it has grown in popularity in countries like the US and the UK, with an estimated 6% of the former’s population identifying as vegan. Supermarkets in the West have several kinds of plant-based food alternatives, and restaurants offer lots of vegan options.

The US, however, is a separate case in and of itself. Popular investigative accounts like Eating Animals by Jonathan Safran Foer have compelled people to turn into vegetarians or vegans (as the author himself admits). However, others, such as celebrated author Michael Pollan, believe that the moral dilemma of eating animals is somewhat unrealistic at its core, and that the fact that humans have ended up as omnivores is a simple fact of evolution. Both Foer and Pollan agree, however, that the factory farming system in the US, where domestic animals are often mass-reared in inhospitable and cramped conditions, is untenable, as well as a public health and safety nightmare.

This particular situation does share some similarities with animal farming in India, but things are far from identical.

Animal Consumption in India

Created by Starline

If historical reports are to be believed, India has had a sustained interest in vegetarianism much before it rose to prominence in the West. But this is largely linked to Brahmanical vegetarianism, where notions of purity were as relevant as any concern about animal welfare. This type of vegetarianism also did not preclude the consumption of milk and milk products (like yogurt and cheese), and relied on “food taboos” (that is, considering people from ‘lower’ castes who ate meat to be seen as ‘impure’). Its survival into today’s India may be said, then, to rely heavily on casteism. It is not purely an issue of ethics.

Veganism, on the other hand, has been argued to be a purely Western import, with no actual historical basis in India. Industrialised animal farming, it is said, does not exist in India on the same scale as it does in the West, and animals are often raised free-range in places like the grasslands of Andhra Pradesh.

However, this does not mean that large-scale animal farming does not exist in India. In addition to this, there is no centralised law that deals with the issue of animal sacrifice, which, when it occurs en masse around religious occasions and festivities, can seem wasteful. And such large demands for animal sacrifice can be met because we do have large industrial farms, where we produce (as per 2020 statistics) 5.3 MT (million tonnes) of meat and 75 billion eggs. In 2019, 192.49 million cattle were being raised in this country. So animal farming is not really an anti-industrial, sustainable practice in many parts of India, although it may be so in some parts of the country.

It has been argued by animal rights groups and activists that animals are often treated inhumanely in large farms. Egg-laying hens are often housed in tiny battery cages, to cut costs. They live in their own waste, and since such farms have anywhere between 10,000 to 3,00,000 birds, the entire land space becomes heavily polluted, making it unsafe for the animals, the workers, and of course, the consumers who will eventually eat those animal products. In dairy farms, as a documentary by Animal Equality revealed in 2017 (the NGO surveyed 107 farms), bulls are often subjected to cruel treatment for the purpose of semen extraction, and male calves are sold for slaughter (and are not allowed to consume milk). Although beef is not consumed widely in India, it is a very popular export. Cows are often illegally drugged to encourage milk production.

It is not surprising, then, that some Indians (mainly those who are city-based) have taken up the practice of veganism as a more sustainable form of living. But while it does have an admirable goal, veganism is not always the most sustainable alternative.

Veganism in India

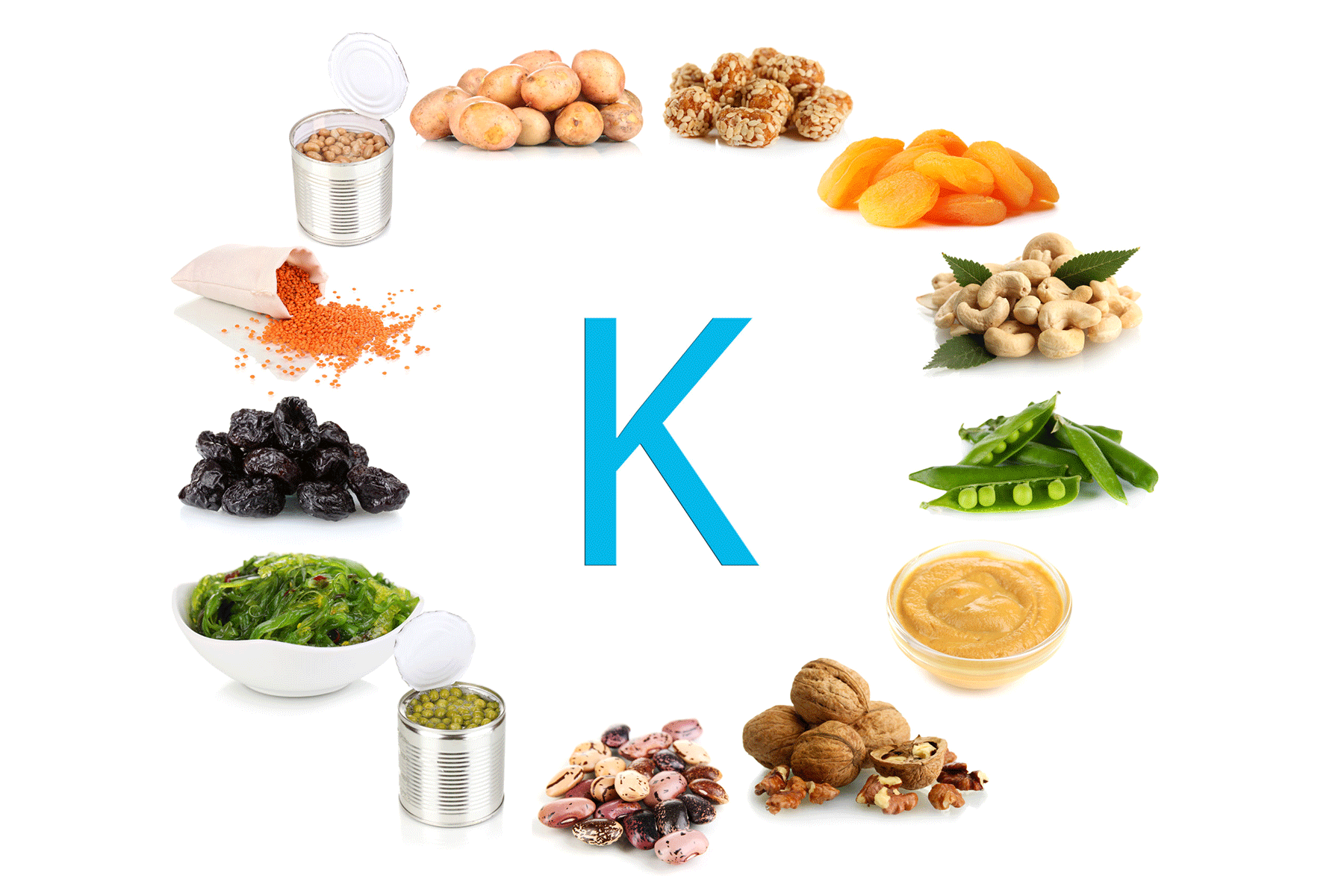

Aside from the fact that eating vegan is a sustainable choice, it is also often seen as a healthier one, when it is done right. Although vegans need to be aware of supplementing their diet with enough iron, calcium, and B12, vegan diets are often nutrient-rich and contain less saturated fat. People who eat a healthy vegan diet rely on an assortment of fruits and nuts, vegetables, beans, and seeds. Such diets are often high in fibre, and since healthy vegans don’t consume much cholesterol, they’re at lower risk of heart disease and stroke, and as they consume fewer calories, they’re less likely to face issues of obesity. However, vegans do have to take regular B12 supplements, and there’s plenty of vegan ‘junk’ food out there that, when consumed on a regular basis, can be just as unhealthy as non-vegan junk food. Aside from B12 and protein deficiency concerns (soy milk still has a lot of protein, though), the vegan diet is certainly one to aspire to for many. And research has proven that vegans, on the whole, smoke and drink less, and exercise more frequently than non-vegans.

However, recent debates on veganism have proven that it is not without its own problems. For example, the mass farming of avocados to meet demands in the West has caused major environmental damage in Mexico. In India, veganism is still a relatively new movement. Plant-based offerings are limited, even in the metropolitan cities. While some foods are naturally vegan, not everyone can afford to buy plant milk or nut butter on a daily basis. And while many have the capacity to alter their diet and lifestyle to fit the criteria of living a plant-based life, others are not placed in the same circumstances.

Going Forward

NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio

As the climate crisis becomes increasingly relevant to our state of living, pushing for large-scale change has become very important. But if you are determined to avoid participating in structures that employ excess animal cruelty, you should investigate where your eggs, dairy, and meat come from, and ensure that your food originates from a place where animals are well-treated and not subject to antibiotics abuse. If you prefer a plant-based diet, alternatives are available, and will become more common in the days to come.

Future challenges, then, must be concerned with engaging with the issue of these industries where mass production leads to abuse and contamination. Regulating these industries rigidly may not be enough in certain areas of the country, and it is undeniable that they provide employment to a large number of people.

The growing trend of veganism may work as an alternative to the problems inherent in factory farming, but it cannot be a solution in and of itself. Food politics in India is always a loaded issue, partially due to religion and caste, but in these divided and environmentally unstable times, it is important that we question where our food comes from, and whether we can continue to live with harmful systems that enable environmental degradation, in light of contemporary debates on the climate crisis.

Food Manifest

Food Manifest

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *