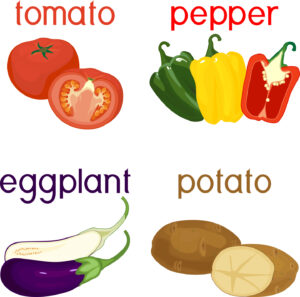

Plant-based diets have gained widespread attention for their health benefits in recent years. However, many people overlook the fact that some plants contain natural toxins that can harm your health. One of the most common and potentially harmful of these is solanine, a bitter toxin present in vegetables like potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers. While these vegetables are dietary staples, solanine protects plants by deterring predators, pests, and disease. Consuming large amounts of solanine, however, can lead to health problems ranging from mild digestive discomfort to severe neurological and gastrointestinal poisoning. This article examines solanine’s role in plants, the symptoms of poisoning, and practical ways to avoid harmful exposure.

What is Solanine?

Solanine, a glycoalkaloid, acts as a natural chemical defense for plants, particularly those in the nightshade family, including potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers. It protects plants from pests, bacteria, fungi, and herbivores. Found in leaves, stems, unripe fruit, and tubers, solanine levels can increase due to environmental factors like light exposure or physical damage. While solanine safeguards plants, it poses risks to humans when consumed in significant amounts. Research indicates that it disrupts cell membranes, damages mitochondria, and interferes with enzyme functions, causing neurological and gastrointestinal issues.

Why Do Plants Produce Solanine?

Plants use solanine as a defence mechanism to deter herbivores, pests, and pathogens by making themselves unpalatable or toxic. They repel insects with this chemical and shield themselves from bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Stress factors like physical damage or light exposure trigger an increase in solanine levels, enhancing the plant’s ability to protect itself. By producing solanine, plants ward off threats and secure their survival and reproduction.

Toxic Effects of Solanine

Consuming high levels of solanine, particularly from potatoes and other nightshade vegetables, can lead to poisoning, which manifests in a range of symptoms from mild to severe:

- Mild symptoms may include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, headaches, dizziness, and stomach cramps, which often resolve with reduced exposure.

- Severe symptoms can involve more serious conditions such as cognitive impairment, hallucinations, confusion, loss of sensation, paralysis, cardiac arrest, or even death in extreme cases if left untreated.

Additionally, prolonged or repeated exposure to smaller amounts of solanine can accumulate in the body over time, potentially contributing to chronic health issues such as autoimmune disorders, neurological imbalances, and intestinal permeability (commonly known as “leaky gut”), which may exacerbate digestive problems and systemic inflammation.

How Much Solanine is Harmful?

The amount of solanine required to cause poisoning depends on factors like body weight and overall health. While small amounts typically don’t cause immediate harm, repeated exposure can lead to a dangerous accumulation of solanine in the body over time, increasing the risk of poisoning.

- Mild poisoning can occur with doses as low as 2 to 5 mg per kilogram of body weight.

- Fatal poisoning is possible when doses exceed 6 mg per kilogram.

Commercial potatoes are typically grown to ensure solanine levels remain within safe limits, but improper storage or consuming green, sprouting, or damaged potatoes can result in dangerously high concentrations of this toxin.

Identifying Solanine in Plants

Nightshade vegetables, including potatoes, tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers, commonly contain solanine. Physical signs often indicate its presence in these plants:

- Green Color in Potatoes: Light exposure triggers solanine concentration in the green parts of potatoes. Although the green hue comes from chlorophyll, it also signals solanine, a natural toxin.

- Sprouts and Damaged Areas: Solanine levels rise in sprouts and damaged parts of the plant. Discarding these sections minimizes exposure.

- Unripe Fruits: Green, unripe tomatoes and eggplants hold higher solanine levels, which decrease as the fruits ripen.

- Peels and Skin: Potato skins typically contain the most solanine. Peeling potatoes before cooking helps reduce the risk.

By being aware of these visual indicators, you can better identify and avoid solanine in plants.

Preventing Solanine Poisoning

To minimize solanine poisoning, follow these guidelines:

- Avoid Eating Green or Unripe Nightshades: Ensure potatoes and other nightshades are ripe before consumption. Avoid any that appear green or underdeveloped.

- Remove Green Parts: If you must eat a slightly green potato, peel it carefully to remove the skin and any sprouts.

- Store Vegetables Properly: Keep potatoes in a cool, dark, dry place. Light exposure increases solanine production, so store them away from light.

- Cook Carefully: While cooking doesn’t eliminate solanine, methods like deep frying at high temperatures can reduce its levels more effectively than boiling.

Conclusion

Solanine poisoning remains an overlooked but significant risk associated with consuming certain nightshade vegetables, especially when improperly stored or consumed in an unripe or damaged state. Though solanine plays a vital role in the plant’s defence system, it can have harmful effects on human health, including digestive and neurological problems, and in extreme cases, death. To reduce the risk of exposure, avoid eating green or sprouting potatoes, remove green parts of nightshades, and store these vegetables properly. By handling and preparing these plants mindfully, we can continue to enjoy their nutritional benefits without compromising our health.

Food Manifest

Food Manifest