The onset of a global pandemic resulted in a chaotic upheaval of the way we used to live. And in a country with extremes of poverty like ours, it wasn’t surprising that daily-wage labourers were hit pretty hard. Vendors who set up panipuri and chaat stalls, fruit and vegetable sellers, and local bazaars contribute majorly to what we consume on a daily basis. Even though supermarkets are a dime a dozen now, especially in urban areas and metropolitan cities, many of us are still accustomed to picking seasonal fruits from a street vendor, or going to bazaars to shop for our fish and poultry, or stopping for a quick cup of tea at a food stall before heading off to work.

Some cities are particularly famous for their street food as well. Kathi roll and panipuri stands litter the streets of Kolkata, chaat stands are a common sight everywhere, but especially in Delhi, and Mumbai workers often stop by for a bite of vada pao before going to their offices. Of course, heartier, healthier options are always available, and this has been a lifesaver for people who don’t live in flats large enough to accommodate kitchens, for students living away from their families, or just for those who don’t have time to prepare meals at certain times in the day. Unlike fancy restaurants, street food stalls and vendors welcome anyone, no matter their position in the class hierarchy, so poorer sections of society have easy and cost-effective access to food.

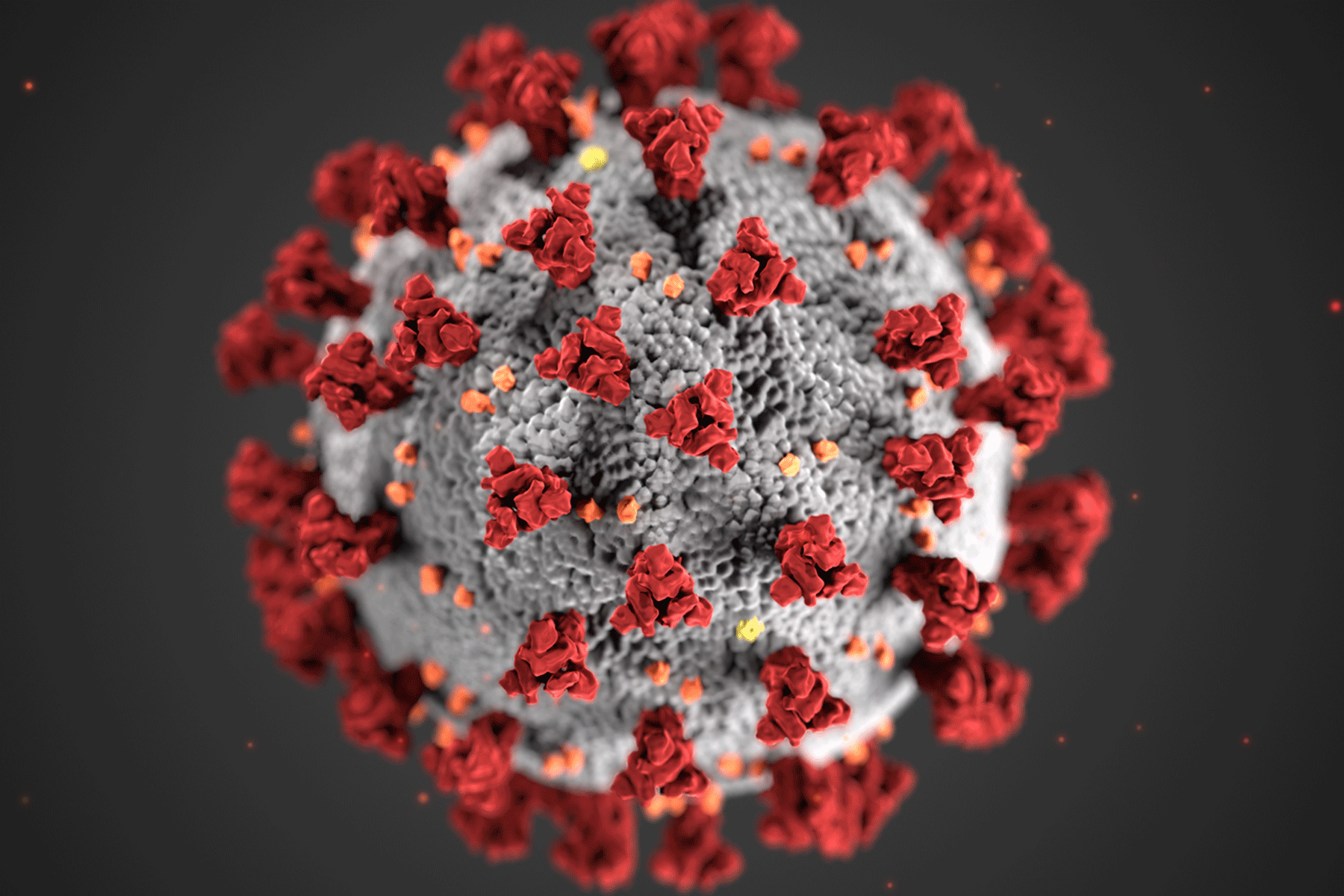

But with the advent of Covid-19, everything changed quite abruptly.

The first wave

A 2020 article reported that there are some 50-60 lakh food vendors across India, many of them migrants. The government’s snap decision to shut down the country on March 24, 2020, due to the spread of the Covid-19 virus, drew much criticism for its lacklustre execution, not least because there had been little thought given to how daily-wage labourers would still make a living. In the months that followed, images of migrants making the long, torturous journey to their homes, often by foot (as travel by bus and rail was no longer an option), dominated the news media. Despite the fact that that dreaded first wave is now behind us, it seems that food vendors still have quite a struggle to face.

Not only did these vendors have to deal with a total shutdown of business, they also had to see to their medical needs, and to the needs of their families. Many migrant workers were forced to depart from the cities to their villages, not only because they had to seek alternate means of income, but also because they feared the virus and its exponential growth in congested cities. Many faced starvation, and had no social influence in the city outside of their vendor communities, and were forced to take loans.

Prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, food vendors and markets did a brisk business, even though they were often subject to social marginalisation, as well as to harassment by the law enforcement. But the return to anything close to the definition of ‘normal’ has proven to be an impossibility.

Returning to business

Although they were not always strictly permitted to do so, (even in August 2020, the Maharashtra government, for example, had no plans to allow street vendors to return to selling their wares), many food vendors did return to work out of desperation. It took several months for restrictions to ease across the country. In the meantime, food vendors were initially not provided any relief package. A credit scheme of Rs. 5000 crore was subsequently announced, although many hawkers’ unions, such as those in Maharashtra, protested that this would not be enough to feed people long-term.

Aside from fruit and vegetable sellers, who have been slightly better off (their work was deemed essential), many vendors who returned to work faced several challenges. They could no longer rely on a higher income during festival seasons, as most public festivities in the initial year of Covid-19 were either cancelled or curtailed. They also had issues obtaining supplies. Some food vendors required specialised ingredients, but due to the fact that the economic life of the country as a whole had come to a halt, the supply chain was broken. The availability of fewer supplies naturally caused a price inflation for supplies that were available, and having faced months of little to no work, food vendors could no longer afford to meet those demands. If they could, they had to price their food items higher (not to mention taking into consideration consistent sanitation procedures), a cost customers would not necessarily be willing to pay.

To compound existing issues, digital apps like Swiggy and Zomato now have an immense presence in the urban food scene. Food vendors in Kolkata mentioned their own lack of digital literacy, and many don’t have fancier smartphone models, but get by with basic ones. In earlier years, when business was steady, food vendors did not think it particularly necessary to get on board with food delivery apps. News reports have noted that both Swiggy and Zomato are partnering with government schemes to bring street vendors onto their platforms. However, it is unclear how this will square with recent controversies which both businesses are facing, as employees have complained of low pay and difficult working conditions.

Present circumstances

Although the situation is not as dire as it was last year, many food vendors and stall owners are not optimistic. Some do report that sales have improved greatly since the onset of the pandemic, although that does not come anywhere close to the profits they made in pre-Covid times. With the present normalisation of hybrid work schedules and work from home routines, customers are no longer lining up to their favourite street food stall. They order their groceries online, and order dinner in. There are fewer evening jaunts to tea stalls to catch up with friends and co-workers. Irregular train schedules mean that other daily-wage labourers who often subsist off street food or local food vendors’ fare no longer line up for a morning meal.

Several night curfews in some states brought their own issues, as food vendors had to shut down their businesses by around 8 pm, at a time when they might ordinarily be drawing more customers.

Organisations like the National Association of Street Vendors of India have spearheaded programs in Delhi, so street vendors can be trained to keep their spaces clean and disinfected, invest in water dispensers, and provide online payment options. While these vendors are eager to relaunch their businesses and are willing to make these significant investments, social distancing, especially in markets, remains an issue.

Moving forward

It is difficult to predict how such a huge (and informal) industry can recover from this blow. The Covid-19 pandemic has been a nightmare for daily-wage labourers in particular, and government support has been slow to come and not nearly enough. Some vendors who used to cook and sell street food now survive by selling vegetables or the like, while others are hardly receiving more than a few customers. The fear of subsequent waves has the entire country on tenterhooks, but a larger awareness of how this pandemic has made the poor even poorer is necessary.

Many street vendors have complained of how they are constantly at odds with the law enforcement, despite being a regular fixture of the food scene on the streets. Their sector is informal in many senses; many food vendors do not possess licenses. No doubt the challenges of the past year have worn them down. Simultaneously, rising Covid cases are also a significant and logical deterrent. Perhaps we cannot go out as frequently as we like to interact with our neighbourhood chaat-wallah, but we can publicise our favourite street food vendors on social platforms and support NGOs that are carrying out programs to help food vendors. For example, the One Rupee Foundation is donating gloves to street vendors in Delhi, while V-LEAD in Mysore is training vendors to form self-help groups, so they don’t rely as much on money-lenders.

Although there are no immediate or all-encompassing solutions to this problem, it is necessary to acknowledge that street food has always been an integral part of our country’s cultural heritage, and that our larger issues of national poverty, negative attitudes towards migrants, and elite class conditioning require more healthy citizen and government engagement.

Food Manifest

Food Manifest

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked with *